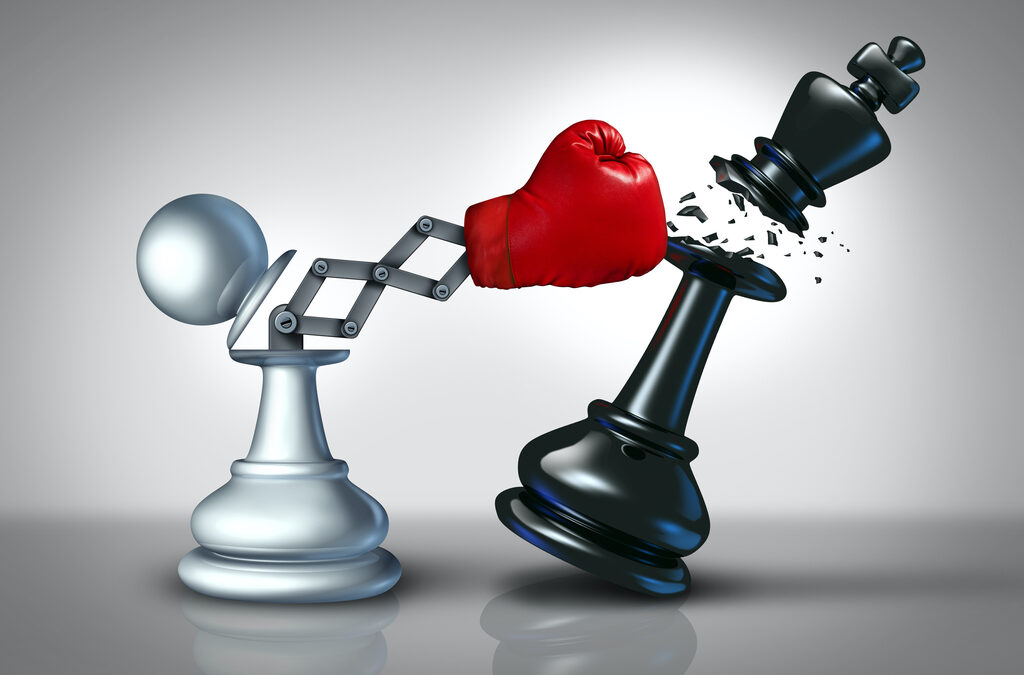

ADR: get one jump ahead

One of my favourite television adverts was the genius O2 campaign “Be More Dog”. You might remember that it follows a day in the life of a cat: “I used to be a cat, aloof till lunch then coldly indifferent after”. Suddenly the cat realises its tedious existence could be fun if only it could “be more dog”. Cue the cat, its head now on a dog’s body, launching out the cat flap to Queen’s “Flash”, chasing a ball, catching a frisbee and digging holes (“running… amazing, chasing cars… amazing, sticks… amazing!”). In a comical way, it epitomised what commitment to a change of mindset can achieve.

For years, many dispute resolution lawyers have been beating the mediation drum, seeking to change the mindset of those litigation lawyers of a more traditional courtroom culture. The COVID crisis has put mediation, particularly online, in the spotlight. For the first time, the global dispute resolution community of mediators, arbitrators, litigators and others are widely promoting mediation as an effective and appropriate way of managing the huge surge in litigation, and the backlogs in civil justice generated by the crisis.

Scotland: stuck in a tunnel

However, in Scotland, the uptake of mediation remains comparatively low. In the US, perhaps surprisingly, the majority of disputes (for example around 98% of litigated cases in California) are mediated as soon as court proceedings are commenced. That’s largely influenced by costs not automatically following success, and the prevalence of lawyers charging contingency fees. In England, parties are often incentivised to mediate due to the potential for adverse judicial costs (expenses) awards if a reasonable offer to mediate is refused. In some regions of Ontario, Canada, mediation has been a mandatory and automatic stage in the court process for 20 years. This could soon be extended to the whole province, following support from the Ontario Bar Association.

In Scotland, mediation is an entirely voluntary process, requiring both or all parties to consent to engage in. There are no incentives to consider or recommend mediation, as there are England. Nor do we have a culture of contingency fees which aligns the lawyers’ interests in getting paid with the clients’ interests in a quicker and more cost effective resolution. So, while it is common for one party to a dispute to advocate for mediation, in reality getting all parties round the table is often a negotiation in itself.

There may soon be some light at the end of the tunnel. The Scottish Government plans to consult on the proposals of the Scottish Mediation Report, Bringing Mediation into the Mainstream in Civil Justice in Scotland. In a nutshell that report makes bold recommendations to introduce an element of compulsion to mediate. So, it is possible we will see legislative changes to promote the use of mediation in civil justice in Scotland.

Agree in advance

Until then, transactional lawyers, in-house lawyers and business leaders have a secret weapon at their disposal: the insertion of clear and concise dispute resolution provisions in contracts. A dispute resolution clause is one of the most vital provisions in any contract. It allows the parties to agree within the contract the process to be followed in the event a dispute arises. There is much to be said for agreeing how a dispute will be dealt with while the parties are on good terms. Once a disagreement or dispute raises its ugly head, parties are usually less willing to adopt a collaborative approach to the process of resolving their differences.

Multi-tiered dispute resolution clauses (sometimes called dispute escalation clauses) are increasingly used by businesses, enterprises and organisations across all sectors and in a wide range of contracts to assist with resolving disputes quickly, efficiently and cost-effectively, and potentially preserving the contractual relationship. Such clauses allow a claim to be escalated in stages, typically by binding the parties to engage first in negotiation at different levels within each party’s business, followed by mediation, as a precondition to arbitration or litigation. Often the clauses will go further and name the organisation from which a mediator (and arbitrator) must be chosen, thereby preventing further potential for disagreement and delay in choosing a third party neutral (www.squaringcirclesodr.uk/dispute-resolution-clauses/).

Provided the terms of a dispute resolution clause are sufficiently clear to create an enforceable obligation, the courts will enforce the terms the parties agreed when they executed the contract. While there have been no reported decisions on the enforceability of such clauses in Scotland (perhaps an indication that they are not used nearly enough), in a number of decisions in the English courts over the last 20 years, parties have been prevented from progressing with court proceedings where the dispute resolution clause has created a contractual obligation to engage in mediation as a condition precedent to litigation. There is no reason to believe the Scottish courts would have decided these cases any differently.

This article first appeared in the October 2020 edition of The Journal of the Law Society of Scotland

Recent Comments